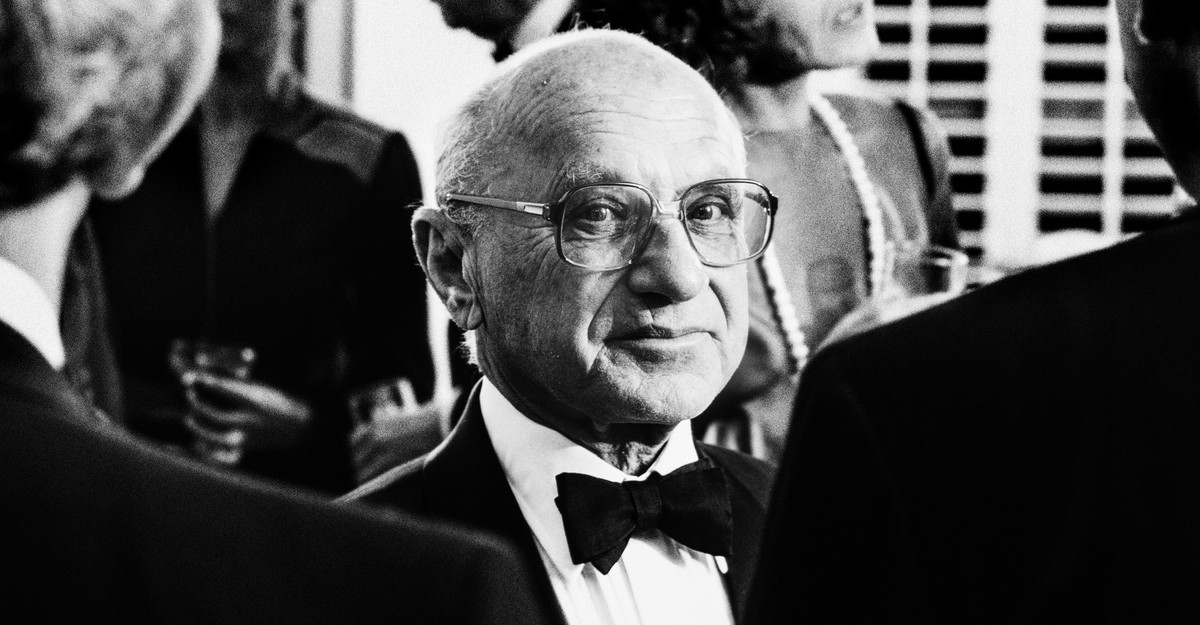

Well earlier than Milton Friedman died in 2006 at 94, he was the uncommon economist who had develop into a family title. A longtime professor on the College of Chicago, he had been writing a column for Newsweek for a decade when he received the 1976 Nobel Prize in economics. Then, in 1980, his PBS collection, Free to Select—a didactic, but by no means dry, paean to the free market—made the diminutive, bald economist one thing of a star.

The weirdness of the present is tough to convey, however “Created Equal,” the fifth of 10 episodes, is consultant of its blunt, unwonky method. The episode opens with pictures of wealth and poverty in India. Friedman’s voice-over reminds us that inequality has been a subject of human concern for a whole bunch of years, courtesy of do-gooders who declare that the wealth of the wealthy rests on the exploitation of the poor. “Life is unfair,” he says. The digital camera then zooms in on Friedman, sitting in a seminar room. “There’s nothing honest about Muhammad Ali having been born with a expertise that permits him to make thousands and thousands of {dollars} one night time. There’s nothing honest about Marlene Dietrich having nice legs that all of us wish to watch.” His voice drops only a bit, and he gazes instantly on the digital camera as if peering into the viewer’s soul. “However alternatively, don’t you assume lots of people who like to take a look at Marlene Dietrich’s legs benefited from nature’s unfairness in producing a Marlene Dietrich?”

As we speak, Friedman may appear to belong to a bygone world. The Trumpian wing of the Republican Celebration focuses on weapons, gender, and God—a stark distinction with Friedman’s free-market individualism. Its hostility to intellectuals and scientific authority is a far cry from his grounding inside educational economics. The analysts related to the Claremont Institute, the Edmund Burke Basis, and the Nationwide Conservatism Convention (similar to Michael Anton, Yoram Hazony, and Patrick Deneen) espouse a imaginative and prescient of society centered on preserving communal order that appears very totally different from something Friedman, a self-defined liberal within the model of John Stuart Mill, described in his work.

A lot of Friedman’s core coverage arguments concerning the virtues of markets had been finally influential amongst neoliberals similar to Invoice Clinton, not simply on the correct. However by now, his central claims (particularly about inflation and the cash provide) have been broadly criticized by economists. And at the least some coverage makers have distanced themselves from his anti-regulatory stances. As Joe Biden declared on the marketing campaign path in 2020, “Milton Friedman isn’t operating the present anymore!”

Jennifer Burns, a Stanford historian, units out to make the case in her intriguing biography Milton Friedman: The Final Conservative that Friedman’s legacy can’t be shaken so simply. As she factors out, a few of his concepts—the volunteer military, faculty selection—have been adopted as coverage; others, similar to a common primary revenue, have supporters throughout the political spectrum. Friedman’s thought, she argues, is extra advanced and refined than has been understood: He raised urgent questions concerning the market, individualism, and the function of the state that will likely be with us for so long as capitalism endures.

Burns’s effort to recast the brash economist as a nuanced analyst usefully situates him in his Twentieth-century context. His profession, it seems, owed a stunning quantity to the New Deal establishments he spent a lot of his life critiquing, and to collaborations that complicate his dedication to unencumbered individualism. However Burns skirts the Twenty first-century legacy of the Friedmanite view of the world: His libertarian ethos helped seed the way more overtly hierarchical social and political conservatism that fuels a lot of our present-day political dysfunction.

Friedman was born in Brooklyn in 1912, the one son of Jap European immigrants who quickly moved to Rahway, New Jersey, the place they owned a dry-goods retailer. His was one of many few Jewish households on the town, and Friedman was observant as a younger baby, however by the point he was an adolescent, he had largely deserted faith. He stood out as a math whiz in highschool and found economics as an undergraduate at Rutgers College. Heading on to graduate faculty on the College of Chicago, he arrived simply in time for the Nice Despair.

Economics as a self-discipline was then within the throes of a metamorphosis. Within the early years of the Twentieth century, reformers had been on the forefront of the sector, keen to construct a social science that will inform authorities coverage. Many economists centered totally on historic statistics, decided to seize how the economic system labored by means of detailed institutional evaluation. However by the Thirties, the main figures on the College of Chicago had been deeply dedicated to what had develop into referred to as value idea, which analyzed financial conduct when it comes to the incentives and data mirrored in costs. The economists who left their mark on Friedman sought to create predictive fashions of financial resolution making, they usually had been politically invested within the excellent of an unencumbered market.

Friedman was additionally formed by older traditions of financial thought, particularly the imaginative and prescient of political economic system superior by thinkers similar to Adam Smith and Alfred Marshall. For them, as for him, economics was not a slim social science, involved with rising productiveness and effectivity. It was intently linked to a broader set of political concepts and values, and it essentially handled primary questions of justice, freedom, and one of the best ways to arrange society.

Simply as necessary, his time at Chicago taught Friedman concerning the intertwining of political, mental, and private loyalties. He grew to become a daily in a casual group of graduate college students and junior school making an attempt to consolidate the division as a middle of free-market thought—the “Room Seven gang,” so named for its conferences in “a dusty storeroom within the economics constructing.” This group, Burns suggests, anticipated the later rise of a “counter-institution” against the regulatory state created by the New Deal. Not that the Chicago economists had been unaffected by the tumult of the ’30s; shaken by the financial institution failures of the winter of 1932, they wrote a memorandum to President Franklin D. Roosevelt shortly after his election that laid out a plan for federal financial intervention to stabilize the monetary system.

Friedman (who went on to put in writing his dissertation at Columbia) headed to Washington, D.C., in 1935, one of many many economists for whom the grim economic system of Despair-era America created a job increase. Throughout World Battle II, he was employed by the Treasury Division, the place he helped introduce the system of federal tax withholding that swelled the nation’s tax base to pay for the conflict.

However his elementary commitments had been constant. In his early work on consumption habits, Friedman sought to puncture the conceitedness of the postwar Keynesian economists, who claimed to have the ability to manipulate the economic system from above, utilizing taxes and spending to show funding, consumption, and demand on and off like so many spigots. As an alternative, he believed that consumption patterns had been depending on native circumstances and on lifetime expectations of revenue. The federal authorities, he argued, may do a lot much less to have an effect on financial demand—and therefore to struggle recessions—than the Keynesian consensus recommended.

In 1946, Friedman was employed by the College of Chicago, the place he shut down efforts to recruit economists who didn’t subscribe to free-market views. He was additionally legendary for his brutal classroom tradition. One departmental memo, making an attempt to rectify the state of affairs, went as far as to remind school to please not deal with a college pupil “like a canine.” What had began as a freewheeling, rebellious tradition among the many economists in Room Seven wound up as doctrinal rigidity.

Yet, as Burns’s analysis has revealed, the intensely private nature of the economics discipline additionally fostered surprising alliances in Friedman’s case: Ladies colleagues—a rarity on the time—got here to play an underappreciated function in his improvement. Then, much more than now, having a robust mentor was an excellent asset within the technique of writing a dissertation and discovering a job—an asset much less obtainable to the few feminine graduate college students in a division that had a single lady professor. Rose Director, a type of few and the intellectually precocious youthful sister of Friedman’s shut buddy and colleague Aaron Director, went the all-but-dissertation route, recognizing the obstacle-strewn path to ending her diploma and getting employed. She and Friedman had fallen in love, and after marrying him in 1938, she went on to play a central half in Friedman’s mental life as transcriber, interlocutor, reader, and editor.

Friedman’s internal circles included different girls colleagues, due to his early give attention to consumption economics—an space that, given the gendered assumption that family bills fell inside girls’s purview, attracted an uncommon proportion of feminine economists. Burns notes that Friedman’s work on the everlasting revenue speculation drew on their Nineteen Forties analysis into the social elements that affect particular person client’s choices. Proof leads her to argue extra pointedly that Rose (credited solely with offering “help”) primarily co-wrote Capitalism and Freedom (1962). She additionally calls consideration to Friedman’s lengthy and fruitful collaboration with Anna Jacobson Schwartz, who had gotten her grasp’s diploma in economics from Columbia and had the identical educational adviser as Friedman. Schwartz helped spur his curiosity in financial economics and shared her analysis with him, even whereas struggling to discover a sponsor for her personal dissertation. She was awarded her Ph.D. solely when Friedman intervened on her behalf after the publication, in 1963, of their co-authored A Financial Historical past of the USA, which boosted his profession when it was in a lull.

Highlighting these dynamics, Burns implicitly exposes a number of the limitations of Friedman’s give attention to the financial advantages of innate particular person expertise. He had greater than nature to thank for producing associates of such excessive caliber, prepared to profit him in his profession. Tradition and establishments clearly performed a big function, and sexual discrimination throughout the Thirties, ’40s, and ’50s ensured that skilled paths had been something however honest.

Even as Friedman criticized the core rules of Keynesianism, he understood the impossibility of merely reverting to the pre-Despair order, as a number of the actually reactionary conservatives of the Nineteen Forties would have preferred. The state, he acknowledged, must take some duty for managing financial life—and thus economists could be thrust right into a public function. The query was what they’d do with this new prominence.

Virtually as quickly because the Second World Battle ended, Friedman started to stake out a particular rhetorical place, arguing that the coverage objectives of the welfare state might be higher achieved by the free market. Earlier skeptics of social reform had argued on the grounds of precept—asserting, for instance, that minimal wages had been unconstitutional as a result of they violated liberty of contract. In contrast, in Capitalism and Freedom, Friedman made the case that the true drawback lay within the strategies liberals employed, which concerned interfering with the aggressive value mechanism of the free market. Liberals weren’t morally fallacious, simply silly, regardless of the vaunted experience of their financial advisers.

In a rhetorical transfer that appeared designed to painting liberal political leaders as incompetent, he emphasised effectivity and the significance of the value system as a device for social coverage. Lease management, for instance, aimed to create inexpensive housing; in actual fact, Friedman maintained, it could limit the housing provide and thus drive rents upward. The minimal wage was supposed to profit employees by creating better-paying jobs; as a substitute, employers would rent fewer employees, rising unemployment. Licensing for medical doctors and dentists was designed to make sure high quality. The impact, although, was to create a monopoly that might increase costs and would guarantee inflated incomes. Even individuals who endorsed liberal objectives wanted to acknowledge that rules, by ignoring the ability of the value system, had been doomed to failure: As an alternative of defending individuals from non-public exploitation, they would go away them on the mercy of the state.

For Friedman, the aggressive market was the realm of innovation, creativity, and freedom. In developing his arguments, he envisioned employees and shoppers as people able to exert decisive financial energy, at all times capable of search a better wage, a greater value, an improved product. The boundaries of this notion emerged starkly in his contorted makes an attempt to use financial reasoning to the issue of racism, which he described as merely a matter of style that must be free from the “coercive energy” of the legislation: “Is there any distinction in precept,” he wrote in Capitalism and Freedom, “between the style that leads a householder to want a lovely servant to an unsightly one and the style that leads one other to want a Negro to a white or a white to a Negro, besides that we sympathize and agree with the one style and will not with the opposite?”

When Friedman wrote about faculty vouchers (his different to common public faculties), he knew that white southerners may use their vouchers to help all-white non-public faculties and evade integration. Though he personally rejected racial prejudice, he thought of the query of whether or not Black youngsters may attend good faculties—and whether or not, given the “style” for prejudice within the South, Black adults may discover remunerative jobs—much less necessary than the “proper” of white southerners to make financial choices that mirrored their particular person preferences. The truth is, Friedman in contrast fair-employment legal guidelines to the Nuremberg Race Legal guidelines of Nazi Germany. Not solely was this tone-deaf within the context of the surging Sixties civil-rights motion; it was an indication of how restricted his concept of freedom actually was.

As the conservative motion began to make electoral positive factors within the ’70s, Friedman emerged as a full-throated challenger of liberal objectives, not simply strategies. He campaigned for “tax limitation” amendments that will have restricted the power of state governments to tax or spend. In a well-known New York Occasions Journal essay, he recommended that firms had no “social duty” in any respect; they had been accountable just for rising their very own income. His PBS collection was proper in keeping with Ronald Reagan’s arrival in workplace—which, predictably, he celebrated. Friedman’s free-market certainties went on to win over neoliberals. By the point he and Rose printed their 1998 memoir, Two Fortunate Individuals, their concepts, as soon as on the margin of society, had develop into the reigning consensus.

That consensus is now in stunning disarray within the Republican Celebration that was as soon as its stronghold. The startling rise in financial inequality and the continued erosion of middle-class dwelling requirements have referred to as into query the concept that downsizing the welfare state, ending rules, and increasing the attain of the market actually do result in larger financial well-being—not to mention freedom. Stepping again, one can see how totally Friedman—regardless of being caricatured as a key mental architect of anti-government politics—had truly internalized an underlying assumption of the New Deal period: that authorities coverage must be the important thing focus of political motion. Utilizing market idea to reshape state and federal coverage was a relentless theme of his profession.

Nonetheless, Friedman—and the libertarian financial custom he superior—bears extra duty for the rise of a far proper in the USA than Burns’s biography would recommend. His technique of goading the left, absolutely on show within the numerous provocations of Free to Select and even Capitalism and Freedom, has been a staple for conservatives ever since. He zealously promoted the type of relentless individualism that undergirds components of immediately’s proper, most notably the gun foyer. The hostile spirit that he delivered to civil-rights legal guidelines surfaces now in the concept that reliance on courtroom choices and laws to handle racial hierarchy itself hems in freedom. The opposition to centralized authorities that he championed informs a political tradition that venerates native authority and personal energy, even when they’re oppressive. Maybe most of all, his insistence (to cite Capitalism and Freedom) that “any … use of presidency is fraught with hazard” has nurtured a deep pessimism that democratic politics can supply any path to redressing social and financial inequalities.

If you purchase a guide utilizing a hyperlink on this web page, we obtain a fee. Thanks for supporting The Atlantic.